How to scaffold models from an ERD in Rails

04 April 2021

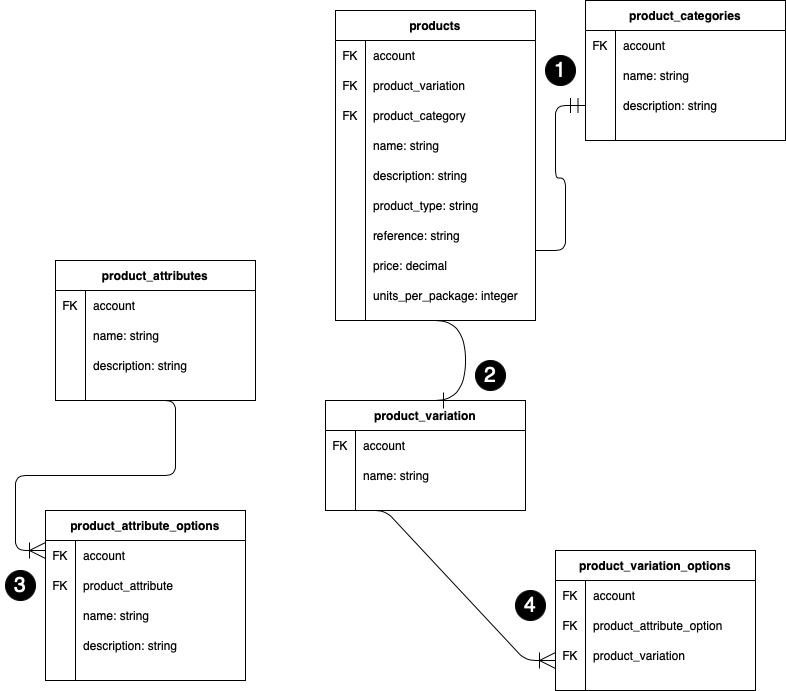

One of the features I love the most about Rails is the ability to quickly scaffold my models into an instant out-of-the-box CRUD interface. The way I would go about this procedure is first to create a barebones Entity Relationship Diagram. The following image depicts one of the diagrams I might create:

This is a slice of a schema belonging to a tailor-made CRM project. And it’s my own brand of ERD diagram. One that helps me to generate the proper model scaffoldings. I’m not interested in specifying all the possible relationships between tables. Only the ones that could or will have an impact on my Rails code. So for example, a product_category can have zero or many products in it, but since I’m not specifying that association on the code then I’m not interested in making that distinction in my diagram either. We’ll go over the numbered references in a bit.

I.- The first couple of questions that pop in my head after completing the diagram are: how do I translate this ERD into a set of rails generate commands? For which entities I need to generate a scaffold and for which entities I need to generate just a model?

The answer I came up with so far is the following: You only rails g model instead of a full scaffold in the following cases:

A.- For models that are actually cross-reference or junction entities as in the case of product_variation_options.

This first case should be pretty self-explanatory. Let’s dive a bit into the schema to understand it. Let’s use a t-shirt as an example of a product. A t-shirt has_one product_variation. A product_variation is a collection of product_attribute_options each of which belongs to a product_attribute. A few examples of t-shirt product_attributes are: size (and the product_attribute_options of size could be something like: small, medium, large) and color (red, blue, black, white). So a product_variation would be a collection of product_attribute_options: Red large t-shirts. So in the ProductVariation model we could have something like:

class ProductVariation < ApplicationRecord

belongs_to :account

has_many :product_attribute_options, through: :product_variation_options

endWe need product_variation_options as a junction or cross-reference entity in order to associate each variation with a number of product_attribute_options. One may ask what’s the point of having a product_variation table to begin with. Why can’t we simply assert that a product has_many product_attribute_options. Well, on one hand imagine a product has lots of attributes attached to it. Then you would need to set all the options when creating it. If we bundle them then it’s a matter of selecting the variation (i.e: Red large V neck). And on the other hand, it’s a handy way of retrieving data from different products that may have the same set of product_attribute_options. Of course you can always get that same data by adding several options to a search filter, but I think it’s cleaner to have a separate variation entity.

In any case, and to come back to the topic at hand, junction or cross-reference entitities like the ones we would put in a through: association like the one above do not need a scaffold. (The reason why I’m using has_many :through instead of has_and_belongs_to_many comes from here).

B.- For models that will become nested attributes of parent models.

A nested attribute is an attribute that you don’t picture yourself filling in an independent view. For example: I can imagine that when I go and create a product_attribute such as size or color then I would add the product_attribute_option on the same page. It wouldn’t make much sense to create a product_attribute and then go on to a different page where I will create a product_attribute_option like large and associate it in a form field to the Size product_attribute and then hit the create button and repeat that process for all my options. So a product_attribute_option is a perfect candidate for a nested attribute and as that, it requires only to generate a model instead of a full scaffold.

II.- The second question one should have is: what attributes do I add into each scaffold or model?

The answer to that question is: all the ones that you have put inside the entity boxes.

The full list of generate commands will look like this:

rails g scaffold ProductCategory name:string description:string account:belongs_to

rails g scaffold ProductAttribute name:string description:string account:belongs_to

rails g model ProductAttributeOption name:string description:string product_attribute:belongs_to account:belongs_to

rails g scaffold ProductVariation name:string account:belongs_to

rails g model ProductVariationOption product_attribute_option:references product_variation:references account:belongs_to

rails g scaffold Product product_type:string name:string reference:string description:string price:decimal units_per_package:integer product_category:belongs_to product_variation:references account:belongs_toNotice that all the foreign keys are added in the commands through a belongs_to or a references association. As far as I know the end result will be the same, which is: they will both add a foreign_key constraint in the table. So for example the Product scaffold command will result in the following ActiveRecord::Migration:

class CreateProducts < ActiveRecord::Migration[6.1]

def change

create_table :products do |t|

t.string :product_type

t.string :name

t.string :reference

t.string :description

t.decimal :price

t.integer :units_per_package

t.belongs_to :product_category, null: false, foreign_key: true

t.references :product_variation, null: false, foreign_key: true

t.belongs_to :account, null: false, foreign_key: true

t.timestamps

end

end

endAnd will generate the following model:

class Product < ApplicationRecord

belongs_to :product_category

belongs_to :product_variation

belongs_to :account

endNotice that in the migration it respects the preferred semantic flavor (it puts t.belongs_to or t.references depending on what we put in the generate command). Yet in the ApplicationRecord it translates the t.references into a belongs_to association.

III.- The third question one should have is: how do you come up with the correct order of commands?

The order of commands simply reflects the order of dependencies. And by this I mean: I can’t scaffold the products before scaffolding the product_variations or the product_categories because I need to set an association (a foreign key to be more precise) within the products table that will reference those two other tables. And the same with the rest of the commands. I first execute the ones that do not depend on any table and I continue from then on.

IV.- The fourth question may or may not arise depending on your Rails expertise. It’s a question I do not have anymore but confused me quite a bit a year ago. And it’s the issue of why I was seeing in some Rails projects a has_one association in a given model instead of a belongs_to?

The answer is that has_one and belongs_to are the two halves of a one-to-one association between two ApplicationRecords. The half where you put the foreign key referencing the other is where you use belongs_to and the half where you show the reverse association you would use has_one. A related question that could pop up is: where do I put the foreign key on this one-to-one case? I found a Toy Story themed example somewhere on stackoverflow that I deem perfect: Andy has_one Woody, but Woody belongs_to Andy. And the foreign key goes into Woody because flipping Woody we’ll find a label with the name ‘Andy’ on it. Well, it was enlightening for me. But I agree it may not work for everyone.

belongs_to of course is used not only for one-to-one associations but also as the half that holds the foreign key of a one-to-many relationship. The above Product model code shows exactly that use case. A product has one product_variation (and in the products table is where you will have the foreign key to the proper product_variation row). But we don’t use has_one because that would mean there’s no foreign key linking a product to a product_variation (a product_variation that could be present in many products).

V.- Fifth issue. Now that we generated the scaffolds and the models. What do we need to change in our Rails code?

And here’s where we will turn our attention to the numbered references in the ERD diagram. The association arrows listed in the diagram are not exhaustive because I want each association vector to correspond with a change in the Rails code that will not be generated automatically with the generate commands. Let’s go over those references now:

1.- Here I highlighted that a product must have a product_category. This does not translate to a change in the code but is something I want to be aware of. Do I really want this association to be mandatory? I add it to the diagram not because I have to change something in the code but because I may change my mind and then I will need to change something in the code.

2.- Here I highlighted that a product may or may not have a product_variation. By default, all belongs_to will be required. But here we’ve decided that a Product may not have a product_variation after all if the product_type is set to simple instead of variable. That’s why we need to change the following line from the CreateProducts migration:

...

t.references :product_variation, null: true, foreign_key: true

...And we have to add an optional flag into our scaffolded model:

...

class Product < ApplicationRecord

...

belongs_to :product_variation, optional: true

...

end3.- A product_attribute can have one or many product_attribute_options. So we need to add that has_many relationship into the product_attribute ApplicationRecord. And we want to destroy the options if the attribute gets deleted so we don’t end up with orphaned attribute options.

...

has_many :product_attribute_options, dependent: :destroy

...Notice we don’t include here some missing changes related to the nature of product_attribute_options as a nested attribute of product_attribute (we’ll tackle that in a different post).

4.- A product_variation can have one or many product_variation_options. Then we go ahead and add that to product_variation ApplicationRecord (we already showed this code snippet above):

...

class ProductVariation < ApplicationRecord

belongs_to :account

has_many :product_attribute_options, through: :product_variation_options

end

...So in a nutshell, after executing the generate commands we’ve taken care of two main issues: changing the flag of any optional belongs_to associations (and we must do this before running the migrations) and also add any necessary has_many associations to the ApplicationRecords (including its dependent: option if required).